With the holiday season upon us, it’s time for conservative media to once again convince us that a city hosting a “Holiday Parade” or a customer service rep uttering the unforgivable phrase “Happy Holidays” represents a full-scale war on Christmas and the baby Jesus himself. In honor of this annual outrage, let’s take a moment to revisit the history of Christmas in the United States. But first, let’s start where it all began—long before Christopher Columbus stumbled his way into the Caribbean thinking he’d found India, all while murdering people who’d been living there long before he showed up with his poor navigational skills.

The Origins of Christmas

Christmas, celebrated as the birth of Jesus on December 25th, first popped up on the scene somewhere around the early to mid-300s AD. The date just so happened to align with the Roman festival Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (The Birthday of the Invincible Sun). With most early Christians living in the pagan Roman Empire, it made sense to hitch their wagon to the most dominant celebration in town. This clever move brought pagans into the church while keeping their festivals mostly intact—because who doesn’t love a good holiday mash-up?

As for the actual birthdate of Jesus, let’s just say biblical scholars are all over the map. The Gospel mentions shepherds in the fields, which likely puts his birth in spring or fall. Some argue the census described in Luke’s Gospel would’ve happened in warmer months to make travel easier. So, was Jesus born on December 25th? Doubtful. But practical? Absolutely.

Now, let’s jump forward a few centuries to the Puritans and their holiday spirit (or lack thereof).

Christmas: Banned in America (Yes, Really)

Despite Fox News’ best efforts, there was actually a time when celebrating Christmas was illegal in America. And no, it wasn’t in San Francisco under some godless, atheist Democrat—it was in Massachusetts under the Puritans, from 1659 to 1681. These deeply devout Christians, obsessed with their particular brand of religious purity, not only outlawed public observance of Christmas but criminalized private celebrations, too. Offenders were fined for their holiday cheer, which is still better treatment than the “witches” got, but authoritarian nonetheless.

The Puritans knew the pagan roots of the holiday (the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti date wasn’t lost on them) and were deeply uncomfortable with its excessively festive nature. Fun, after all, was suspicious. Think of the Puritans as the Christian Taliban of the New World, complete with rules dictating how one should dress, think, and behave. Ho ho ho, indeed.

The 19th Century: Christmas Goes Mainstream

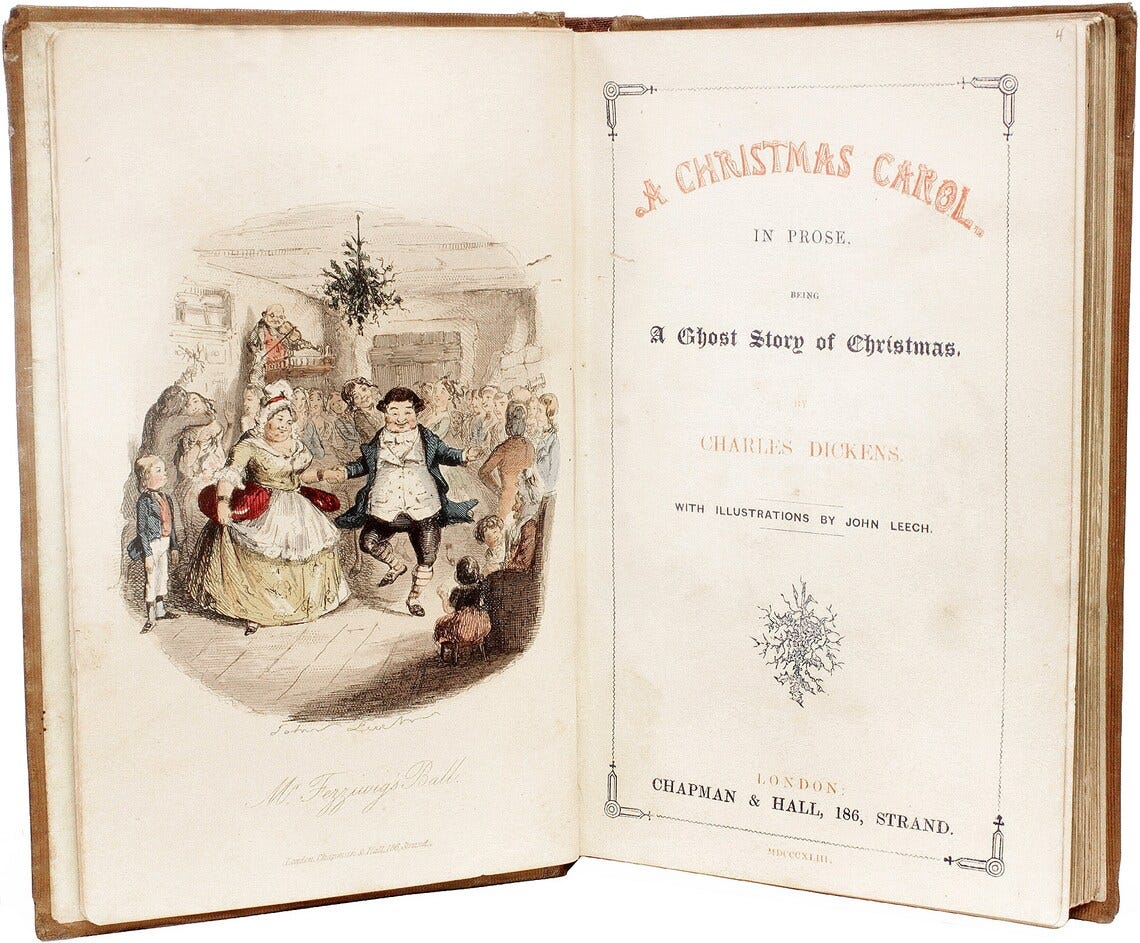

Christmas didn’t truly take off in America until the 1800s. Authors like Washington Irving and Charles Dickens played a huge role in rehabilitating the holiday’s image. Irving’s writings depicted Christmas as a peaceful, harmonious celebration rooted in English tradition, while Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843) gave us Tiny Tim, Scrooge, and themes of generosity and goodwill that Americans couldn’t resist.

Meanwhile, German immigrants brought one of the most iconic symbols of Christmas—the Christmas tree. At first, the tree was limited to German-speaking communities, but in 1848, a single image changed everything. The Illustrated London News published a drawing of Queen Victoria and her German-born husband, Prince Albert, standing next to a decorated tree. Suddenly, having a Christmas tree became fashionable on both sides of the Atlantic.

Santa Claus: From Saint to Marketing Legend

Santa Claus has one of the most fascinating (and capitalist-friendly) origin stories of all. He’s based on St. Nicholas, a 4th-century Christian bishop from Myra (modern-day Turkey), known for his generosity. Dutch settlers brought their version, “Sinterklaas,” to New Amsterdam (now New York) in the 17th century.

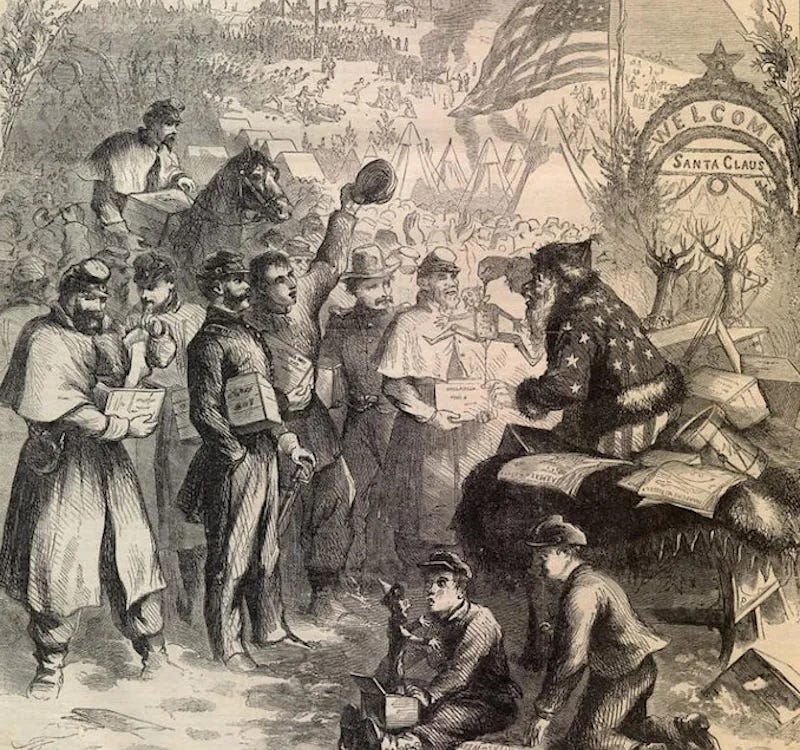

Santa’s transformation into the jolly old man in red was an American invention. In 1809, Washington Irving jokingly depicted St. Nicholas as a pipe-smoking, gift-delivering figure in a flying wagon. By the 1860s, cartoonist Thomas Nast took it up a notch. His illustrations for Harper’s Weekly introduced us to the Santa Claus we recognize today—plump, bearded, and cheerful, complete with a North Pole workshop, elves, and a naughty/nice list.

Of course, Coca-Cola later leaned into this image, popularizing Santa in their advertising campaigns during the 20th century. Because nothing says “Merry Christmas” like a cold soda.

Christmas Becomes a Federal Holiday

It wasn’t until June 26, 1870, that Christmas became a federal holiday. President Ulysses S. Grant, hoping to foster national unity after the Civil War, signed the legislation. Fun fact: Grant was less concerned with religious significance and more interested in giving everyone a day to chill out and not fight each other. A noble goal.

The White House Christmas Tree

While the Christmas tree tradition was growing in American homes, the White House didn’t get its first official Christmas tree until 1889, during Benjamin Harrison’s presidency. Harrison and his family set up the tree in the Yellow Oval Room, decorating it with candles and toys for their grandchildren. Calvin Coolidge later solidified the tradition by hosting the first National Christmas Tree lighting ceremony in 1923.

So, Where Does This Leave Us?

Christmas in America has a rich, complicated, and downright messy history. From being banned by devout Christians, to being reshaped by literature, immigrants, artists, and, yes, big business, our modern Christmas has grown into a melting pot of traditions. Germans gave us the tree. The Dutch gave us Santa. The British monarchy made it chic. And Ulysses S. Grant made it official. If you squint hard enough, Christmas might just be America’s first Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion holiday—a blend of traditions, cultures, and commercialism coming together under one festive banner.

So this year, if someone wishes you a “Happy Holidays,” maybe take a deep breath and smile. Christmas is big enough to survive the Puritans, capitalism, and even a mildly polite greeting. Let’s not ruin it now.